Narodnaya Volya

People's Will Наро́дная во́ля | |

|---|---|

| Founded | June 1879 |

| Dissolved | March 1887 |

| Split from | Land and Liberty |

| Headquarters | St. Petersburg (1879–1881) Moscow (1881–1882) |

| Membership | 2193[1] |

| Ideology | Narodism Agrarian socialism Revolutionary socialism |

| Political position | Far-left |

| Movement | Narodniks |

| Anthem | Народовольческий гимн ("Hymn of the People's Will")[2] |

Narodnaya Volya (Russian: Наро́дная во́ля, IPA: [nɐˈrodnəjə ˈvolʲə], lit. 'People's Will') was a late 19th-century revolutionary socialist political organization operating in the Russian Empire, which conducted assassinations of government officials in an attempt to overthrow the autocratic Tsarist system. The organization declared itself to be a populist movement that succeeded the Narodniks. Composed primarily of young revolutionary socialist intellectuals believing in the efficacy of direct action, Narodnaya Volya emerged in Autumn 1879 from the split of an earlier revolutionary organization called Zemlya i Volya ("Land and Liberty"). Similarly to predecessor groups that had already used the term "terror" positively, Narodnaya Volya proclaimed themselves as terrorists and venerated dead terrorists as "martyrs" and "heroes", justifying political violence as a legitimate tactic to provoke a necessary revolution.[3]

Based upon a secret society apparatus of local, semi-independent cells co-ordinated by a self-selecting Executive Committee, Narodnaya Volya espoused acts of political violence in an attempt to destabilize the Russian Empire and spur insurrection against Tsarism, justified "as a means of exerting pressure on the government for reform, as the spark that would ignite a vast peasant uprising, and as the inevitable response to the regime's use of violence against the revolutionaries". This culminated in the successful assassination of Tsar Alexander II in March 1881—the event for which the group is best remembered. The group developed ideas—such as the assassination of the "leaders of oppression"—that were to become the hallmark of future small anti-state groups, and were convinced that new technologies such as dynamite enabled them to strike the regime powerfully and precisely, minimising casualties.

Much of the organization's philosophy was inspired by Sergey Nechayev and Carlo Pisacane, the proponent of "propaganda by the deed". The group served as inspiration and forerunner for other revolutionary socialist and anarchist organizations, including in the Russian Socialist Revolutionary Party (PSR). Although they were socialist, they generally opposed Marxism in favour of an ideal of anarchist self-government.

History

[edit]The Populist background

[edit]

The emancipation of the serfs in 1861 did not suddenly end the state of grim rural poverty in the Russian Empire, and the autocracy headed by the Tsar of Russia and the nobles around him, as well as the privileged state bureaucracy, remained in firm control of the nation's economy from which it extracted pecuniary benefits. By the beginning of the 1870s, dissent regarding the established political and economic order had begun to take concrete form among many members of the intelligentsia, which sought to foster a modern and democratic society in Russia in place of the economic backwardness and political repression which marked the old regime.

A set of "populist" values became commonplace among these radical intellectuals seeking change of the Russian economic and political form.[4] The Russian peasantry, based as it was upon its historic village governing structure, the peasant commune (obshchina or mir), and its collective holding and periodic redistribution of farmland, was held to be inherently socialistic, or at least fundamentally amenable to socialist organization.[5] It was further believed that this fact made possible a unique path for the modernization of Russia which bypassed the industrial poverty that was a feature of early capitalism in Western Europe[6]—the region to which Russian intellectuals looked for inspiration and by which they measured the comparatively backwards state of their own polity.

Moreover, the radical intelligentsia believed it axiomatic that individuals and the nation had the power to control their own destiny and that it was the moral duty of enlightened civil society to transform the nation by leading the peasantry in mass revolt that would ultimately transform Russia to a socialist society.[6]

These ideas were regarded by most radical intellectuals of the era as nearly incontestable, the byproduct of decades of observation and thought dating back to the conservative Slavophiles and sketched out by such disparate writers as Alexander Herzen (1812–1870), Pyotr Lavrov (1823–1900), and Mikhail Bakunin (1814–1876).[7]

Socialist study circles (kruzhki) began to emerge in Russia during the decade of the 1870s, populated primarily by idealistic students in major urban centers such as St. Petersburg, Moscow, Kiev, and Odessa.[8] These initially tended to have a loose organizational structure, decentralized and localized, bound together by the personal familiarity of participants with one another.[8] Efforts to propagandize revolutionary and socialist ideas among factory workers and peasants were quickly met with state repression, however, with the Tsarist secret police (Okhrana) identifying, arresting, and jailing agitators.[9]

In the spring of 1874 a mass movement of Going to the People began, with young intellectuals taking jobs in rural villages as teachers, clerks, doctors, carpenters, masons, or common farm laborers, attempting to immerse themselves in the peasants' world so as to better inculcate them with socialist and revolutionary ideas.[10] Fired with messianic zeal, perhaps 2,000 people left for rural posts in the spring; by the fall some 1,600 of these found themselves arrested and jailed, failing to make the slightest headway in fomenting agrarian revolution.[10] The failure of this movement, marked by a rejection of political arguments by the peasantry and easy arrests of public speakers by local authorities and the Okhrana, deeply influenced the revolutionary movement in years to follow.[11] The need for stealth and secrecy and more aggressive measures seemed to have been made clear.

The antecedent organization

[edit]

Following the failure of the 1874 effort at "going to the people", revolutionary populism congealed around what would be the strongest such organization of the decade, Zemlya i Volya ("Land and Liberty"), the prototype of a new type of centralized political organization which attempted to muster and direct every potential aspect of urban and rural discontent.[12] The nucleus of this new organization, which borrowed its name from radicals of the preceding decade, was established in St. Petersburg late in 1876.[12] As an underground political party marked by extreme secrecy in the face of secret police repression, few primary records originating from the group documenting its existence have survived.[13]

Zemlya i Volya is associated in particular with the names of M.A. Natanson (1851–1919), a committed activist from the first half of the decade who both founded the organization and provided it with institutional memory, and Alexander Mikhailov (1855–1884), the leading representative of a new wave of participants and memoirist of the movement.[14] This vanguard party, composed almost exclusively of intellectuals, continued in the tradition of idealizing traditional peasant organization as a pathway to broader social transformation. As Alexander Mikhailov wrote:

The "rebels" idealize the people. They hope that in the very first moments of freedom political forms will appear which correspond to their own conceptions based on the obshchina and on federation... The party's task is to widen the sphere of action of self-administration to all internal problems.[15]

An extensive program was drawn up in St. Petersburg in 1876 calling for the break up of the nations of the Russian Empire, granting of all land to the "agricultural working class", and transfer of all social functions to the village communes.[16] This program warned "Our demands can be brought about only by means of violent revolution", and it prescribed "agitation...both by word and above all by deed—aimed at organizing the revolutionary forces and developing revolutionary feelings" as the vehicle for "disorganization of the state" and victory.[16]

These ideas were borrowed directly from Mikhail Bakunin, a radicalized émigré nobleman from Tver guberniia regarded as the father of collectivist anarchism.[17] In practice, however, a significant percentage of Zemlya i Volya members (so-called Zemlevoltsy), returned to the model of the study circle and concentrated their efforts upon the industrial workers of urban centers.[18] Among these were the young Georgi Plekhanov (1856–1918), an individual later celebrated as the father of Russian Marxism.[19]

Whatever the practical activities of its local groups, the official position of the Zemlya i Volya organization endorsed the tactic of violent direct action, which the lead article in the first issue of the party's newspaper characterized as a "system of mob law and self-defense" put into action by a "protective detachment" of the liberation movement.[20] The group also rationalized political assassination as "capital punishment" and "self-defense" for "crimes" against the nation.[20] The organization began to look at regicide as the highest manifestation of political action, culminating in a December 1879 assassination attempt on Tsar Alexander II by the Zemlevolets A. K. Soloviev (1846–1879).[21]

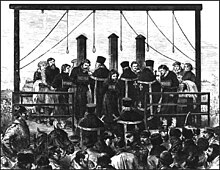

Accelerated state repression of Zemlya i Volya followed the hanging of attempted assassin Soloviev, with arrests nearly wiping out revolutionary cells in the west of the Russian Empire and putting severe pressure on the organization elsewhere.[22] The tension over the use of violence led to a division of the organization, with proto-Marxists who favored an end to the use of violent direct action to gain control over the official newspaper while the activist wing controlled a majority of the Executive Committee.[23] Efforts to reconcile the two wings were unsuccessful and a split was formalized on 15 August 1879, by a commission appointed to divide the organization's assets.[22]

During the latter part of 1879, those favoring study circles and propaganda to build a revolutionary movement from the ground up, exemplified by Plekhanov and his co-thinkers, launched independent activity as a new organization called Chërnyi Peredel (Russian: Чёрный передел, "Black Repartition"). The unrepentantly violent wing re-established itself as well, this time under a new banner—Narodnaya Volya ("People's Freedom", frequently albeit imprecisely rendered into English as "People's Will").[24]

Establishment

[edit]During the first months after its formation, Narodnaya Volya founded or co-opted workers study circles in the major cities of St. Petersburg, Moscow, Odessa, Kiev, and Kharkov.[25] The group also established cells within the military, among the army garrison at St. Petersburg and the Kronstadt naval base.[25] The organization established a party press and issued illegal newspapers in support of its efforts—five issues of the eponymous Narodnaya Volya and two issues of a newspaper targeted to industrial workers, Rabochaia Gazeta (The Workers' Newspaper).[25] A series of illegal leaflets were produced, putting party proclamations and manifestos in the hands of potential supporters.[25]

Narodnaya Volya saw themselves as continuers of the populist tradition of earlier years rather than marking a fresh break from the past, declaring in their press that while they would not keep the title Zemlevoltsy since they no longer represented the earlier party's entire tradition, they nevertheless intended to continue the principles established by the Zemlya i Volya organization and to continue to make "Land and Liberty" their "motto" and "slogan".[26]

The organization promulgated a program which called for "complete freedom of conscience, speech, press, assembly, association, and electoral agitation".[27] The group made the establishment of political freedom its top public objective, with the radical publicist N.K. Mikhailovsky (1842–1904) contributing two finely crafted "political letters" on the topic to two early issues of the party's official organ.[28] The party declared its intention to lay down arms as soon as political concessions were made.[28] There were no dreams of the organization forming the basis of a ruling party, with a fundamental hope maintained in the emergence of the self-governing village commune as the basis of a new socialist society.[29]

The Narodnaya Volya organization also began a violent revolutionary campaign, with the governing Executive Committee issuing a proclamation calling for the execution of Tsar Alexander II for his crimes against the Russian people.[25] While giving lip service to the demand for political freedom and a constitutional republic as its objective, the so-called Narodnovoltsy seem to have actually believed themselves to be pursuing a maximalist program in which violence and political assassination would "break the government itself" and end all vestiges of the Tsarist regime in Russia.[27] The government was seen as weak and tottering, and chances for its revolutionary overthrow promising.[30]

Organizational structure

[edit]Narodnaya Volya continued the trend towards secret organization and centralized direction that had begun with Zemlya i Volya—principles held to tightly in the face of growing government repression of participants in the organization.[31] Democratic control of the party apparatus was deemed impossible under existing political conditions and the organization was centrally directed by its self-selecting Executive Committee, which included, among others Alexander Mikhailov, Andrei Zhelyabov (1851–1881), Sophia Perovskaya (1853–1881), Vera Figner (1852–1942), Nikolai Morozov (1854–1946), Mikhail Frolenko (1848–1938), Aaron Zundelevich (1852–1923), Savely Zlatopolsky (1855–1885) and Lev Tikhomirov (1852–1923).

The Executive Committee was in existence for six years, during which time it was populated by less than 50 people, including in its ranks both men and women.[32] The official membership of the Narodnaya Volya organization during its existence has been estimated at 500, bolstered by an additional number of informal followers.[33] A document listing the movement's participants, including those from the period from 1886 to 1896 when only a small skeleton organization remained, totals 2,200.[34]

Assassination of Tsar Alexander II

[edit]

The assassination of Tsar Alexander II on 13 March [O.S. 1 March] 1881 marked the high-water mark of Narodnaya Volya as a factor in Russian politics. While the assassination did not end the Tsarist regime, the government ran scared in the aftermath of the bomb that killed him, with the formal coronation ceremony of Tsar Alexander III postponed for more than two years due to security concerns.[35]

The Tsar had been formally sentenced to death by the Executive Committee of Narodnaya Volya on 25 August 1879, on the heels of the execution of former Zemlevolets Solomon Wittenberg, who had attempted to build a mine to sink a ship carrying the Tsar into Odessa harbor the previous year.[36] An initial plan called for the use of dynamite to destroy a train carrying the Tsar, which ended with an explosion that destroyed a freight car and led to a derailment.[37] A February 1880 attempt used a quantity of dynamite to attempt to blow up the Tsar in a palace dining room. The resulting explosion killed 11 guards and soldiers and wounded 56, but missed the Tsar, who was not in the dining hall as expected.[38]

A state of siege followed, during which the demoralized Tsar avoided public appearances amidst sensational rumors in the press of additional attacks in the offing.[39] One French diplomat likened the Tsar to a ghost—"pitiful, aged, played out, and choked by a fit of asthmatic coughing at every word".[39] In response to the security crisis the Tsar established a new Supreme Commission for the Maintenance of State Order and Public Peace, under the command of Mikhail Loris-Melikov, a hero of the Russo-Turkish War.[40] Just over a week later, a Narodnovolets attempted to assassinate Loris-Melikov with a handgun, firing a shot but missing, only to be hanged two days later.[40] Repression was ratcheted upwards, with two Narodnaya Volya activists executed in Kiev the following month for the crime of distributing revolutionary leaflets.[40]

See also

[edit]- Government reforms of Alexander II of Russia

- Russian nihilist movement

- Socialist Revolutionary Party

- Group of Narodnik Socialists

- Nakanune (newspaper)

- Nikolai Danielson

- Zemlya i Volya

References

[edit]- ^ Hertz, Deborah (2014). "Dangerous Politics, Dangerous Liaisons: Love and Terror among Jewish Women Radicals in Czarist Russia". Histoire, économie & société (in French). 33 (4): 96. doi:10.3917/hes.144.0094. ISSN 0752-5702.

- ^ "Народовольческий гимн". narovol.narod.ru.

- ^ Dafinger, Johannes; Florin, Moritz (2022). A Transnational History of Right Wing Terrorism: Political Violence and the Far Right in Eastern and Western Europe since 1900. United Kingdom: Routledge.

- ^ Offord 1986, p. 1.

- ^ Offord 1986, pp. 1–2.

- ^ a b Offord 1986, p. 2.

- ^ Offord 1986, pp. 2–3.

- ^ a b Offord 1986, p. 16.

- ^ Offord 1986, pp. 16–17.

- ^ a b Offord 1986, p. 17.

- ^ Offord 1986, p. 18.

- ^ a b Venturi 1960, p. 558.

- ^ Venturi 1960, pp. 558–559.

- ^ Venturi 1960, pp. 562–563.

- ^ Venturi 1960, p. 572.

- ^ a b Venturi 1960, pp. 573–574.

- ^ Offord 1986, p. 19.

- ^ Offord 1986, p. 21.

- ^ Offord 1986, pp. 21–22.

- ^ a b Offord 1986, p. 24.

- ^ Offord 1986, p. 25.

- ^ a b Yarmolinsky 2014, p. 229.

- ^ Yarmolinsky 2014, p. 228.

- ^ Offord 1986, p. 26.

- ^ a b c d e Offord 1986, p. 28.

- ^ Offord 1986, p. 32.

- ^ a b Offord 1986, pp. 28–29.

- ^ a b Offord 1986, p. 29.

- ^ Offord 1986, p. 33.

- ^ Offord 1986, p. 34.

- ^ Offord 1986, p. 30.

- ^ Yarmolinsky 2014, p. 233.

- ^ Yarmolinsky 2014, pp. 234–235.

- ^ Yarmolinsky 2014, p. 234.

- ^ Offord 1986, p. 36.

- ^ Yarmolinsky 2014, p. 250.

- ^ Yarmolinsky 2014, pp. 252–57.

- ^ Yarmolinsky 2014, pp. 259–60.

- ^ a b Yarmolinsky 2014, p. 261.

- ^ a b c Yarmolinsky 2014, p. 262.

Bibliography

[edit]- Offord, Derek (1986). The Russian Revolutionary Movement in the 1880s. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521327237. OCLC 802697258.

- Venturi, Franco (1960) [1952]. Roots of Revolution: A History of the Populist and Socialist Movements in Nineteenth-Century Russia. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson.

- Yarmolinsky, Avrahm (2014) [1956]. "The People's Will". Road to Revolution: A Century of Russian Radicalism. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. pp. 223–241. ISBN 978-0691610412. OCLC 890439998.

Further reading

[edit]- James H. Billington, Mikhailovsky and Russian Populism. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1958.

- Leopold H. Haimson, The Russian Marxists and the Origins of Bolshevism. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1955.

- J. L. H. Keep, The Rise of Social Democracy in Russia. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1963.

- Evgeny Lampert, Sons Against Fathers: Studies in Russian Radicalism and Revolution. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1965.

- Philip Pomper, Peter Lavrov and the Russian Revolutionary Movement. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1972.

- Philip Pomper, The Russian Revolutionary Intelligentsia. New York: Thomas Y. Crowell, 1970.

- Robert Service, "Russian Populism and Russian Marxism: Two Skeins Entangled", in Roger Bartlett (ed.), Russian Thought and Society, 1800–1917: Essays in Honour of Eugene Lampert. Keele, England: University of Keele, 1984; pp. 220–246.

- Hugh Seton-Watson, The Decline of Imperial Russia, 1855–1914. New York: Frederick A. Praeger, 1952.

- Astrid Von Borcke, "Violence and Terror in Russian Revolutionary Populism: The Narodnaya Volya, 1879–83." in Gerhard Hirschfeld and Wolfgang J. Mommsen, (eds.) Social Protest, Violence and Terror in Nineteenth-and Twentieth-century Europe (Palgrave Macmillan, 1982) pp. 48-62.

- Andrzej Walicki, The Controversy Over Capitalism: Studies in the Social Philosophy of the Russian Populists. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1969.

- Andrzej Walicki, A History of Russian Thought from the Enlightenment to Marxism. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1980.

- US congress, report of the committee of foreign affairs on H.R 11356. 25 May 1956

- Narodnaya Volya

- 1879 establishments in the Russian Empire

- 1887 disestablishments in the Russian Empire

- Far-left politics in Russia

- Organizations disestablished in 1887

- Organizations established in 1879

- Political organizations based in the Russian Empire

- Political parties disestablished in 1887

- Political parties established in 1879

- Politics of the Russian Empire