Graham Taylor

Taylor pictured in 2010 | |||

| Personal information | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Full name | Graham Taylor | ||

| Date of birth | 15 September 1944 | ||

| Place of birth | Worksop, England | ||

| Date of death | 12 January 2017 (aged 72) | ||

| Place of death | Kings Langley, England[1] | ||

| Position(s) | Full back | ||

| Senior career* | |||

| Years | Team | Apps | (Gls) |

| 1962–1968 | Grimsby Town | 189 | (2) |

| 1968–1972 | Lincoln City | 150 | (1) |

| Total | 339 | (3) | |

| Managerial career | |||

| 1972–1977 | Lincoln City | ||

| 1977–1987 | Watford | ||

| 1987–1990 | Aston Villa | ||

| 1990–1993 | England | ||

| 1994–1995 | Wolverhampton Wanderers | ||

| 1996 | Watford | ||

| 1997–2001 | Watford | ||

| 2002–2003 | Aston Villa | ||

| *Club domestic league appearances and goals | |||

Graham Taylor OBE (15 September 1944 – 12 January 2017) was an English football player, manager, pundit and chairman of Watford Football Club. He was the manager of the England national football team from 1990 to 1993, and also managed Lincoln City, Watford, Aston Villa and Wolverhampton Wanderers.

Born in Worksop, Nottinghamshire,[2] Taylor grew up in Scunthorpe, Lincolnshire, which he regarded as his hometown.[3] The son of a sports journalist[4] who worked on the Scunthorpe Evening Telegraph, Taylor found his love of football in the stands of the Old Show Ground watching Scunthorpe United. He became a professional player, playing at full back for Grimsby Town and Lincoln City. After retiring as a result of injury in 1972, Taylor became a manager and coach. He won the Fourth Division title with Lincoln in 1976, before moving to Watford in 1977. He took Watford from the Fourth Division to the First in five years. Under Taylor, Watford were First Division runners-up in 1982–83, and FA Cup finalists in 1984. Taylor took over at Aston Villa in 1987, leading the club to promotion in 1988 and 2nd place in the First Division in 1989–90.

In July 1990, he became the manager of the England team. They qualified for the 1992 European Championship but were knocked out in the group stages. Taylor resigned in November 1993, after the team failed to qualify for the 1994 FIFA World Cup in the United States. Taylor faced heavy criticism from fans and media during his tenure as England manager and earned additional public interest and scrutiny when a television documentary, An Impossible Job, which he had permitted to film the failed campaign from behind the scenes, aired in 1994.

Taylor returned to club management in March 1994 with Wolverhampton Wanderers. After one season at Molineux, he returned to Watford, and led the club to the Premier League in 1999 after back-to-back promotions. His last managerial role was manager of Aston Villa, to which he returned in 2002. He left at the end of the 2002–03 season. Taylor served as Watford's chairman from 2009 until 2012, after which he held the position of honorary life-president. He also worked as a pundit for BBC Radio Five Live.

Early life

[edit]Born in Worksop, Nottinghamshire,[2] Taylor moved in 1947 to a council house in Scunthorpe, where his father, Tom, was the sports reporter for the Scunthorpe Evening Telegraph. He went to the Henderson Avenue Junior School, then Scunthorpe Grammar School (now The St Lawrence Academy), where he met his future wife, Rita, from Winteringham. He played for the England Grammar Schools football team, and joined the sixth-form after passing six O-levels in 1961, but he left after one year to pursue a full-time career in football. His head teacher disapproved of his actions who told him: "Grammar school boys don't become footballers".[5]

Playing career

[edit]His playing career began with as an apprentice for Scunthorpe United.[6] He then went on to join Grimsby Town in 1962 and played his first competitive game for them in September 1963 against Newcastle United when they won 2–1. He played 189 games at fullback for Grimsby Town, scoring twice. He was transferred to Lincoln City in the summer of 1968 for a fee of £4,000, scoring 1 goal in 150 appearances before being forced to retire from playing following a serious hip injury in 1972.

Club managerial career

[edit]Records

[edit]Taylor was the only manager to have twice led teams that amassed over 70 points in one Football League season under the League's original scoring system of two points for a win and one point for a draw. This system was introduced for the inaugural 1888–89 season and was retained for over 90 years until the reward for a win was increased to three points in 1981. He achieved this with Lincoln City (74 points – 1976) and Watford (71 points – 1978).[7] Only two other clubs, Doncaster Rovers (72 points – 1947) and Rotherham United (71 points – 1951), managed to gain over 70 points in one season under the original scoring system.

Lincoln City (1972–1977)

[edit]Taylor was the youngest person to become an FA coach, at the age of 27.[8] Following his retirement from playing, and a spell as player coach, Taylor became manager of Lincoln City, being the youngest manager in the league at the age of 28, on 7 December 1972 after David Herd resigned.[9] In his first season Lincoln finished 10th, then 12th in 1974, but the following season narrowly missed out on promotion after a 3–2 defeat at Southport on 28 April 1975.[10]

Taylor led Lincoln to the Fourth Division title in 1976;[8] his team's 32 wins, 4 defeats and 74 points were all league records (when 2 points were awarded for a win).[11][12] Lincoln finished 9th in the Third Division in 1976-1977 under Taylor.[10]

Watford (1977–1987)

[edit]In June 1977, Taylor was hired to manage Watford by new owner Elton John. He turned down an approach from First Division West Bromwich Albion in favour of the Hertfordshire-based club, then competing in the Fourth Division, surprising pundits and supporters alike. John acted on the advice of Don Revie when hiring Taylor.[13]

Taylor led Watford from the Fourth Division to the First Division in only five years.[14] In his first season Watford won the 1977–78 Fourth Division title, losing only five of 46 games and winning the division by 11 points.[15] In the Third Division Taylor led Watford to another promotion, finishing second, and losing out on the title by one point in the 1978–79 season.[16]

Taylor's third season, in the Second Division, was less successful. Indicating the tougher competition, Watford managed only an 18th finish, out of 22 teams, avoiding relegation by eight points and winning only 12 of their 42 games in the 1979–80 season.[17] In the next season, the 1980–81 season, Taylor improved Watford's performance, ending it with 16 wins and a 9th-place finish.[18] In the 1981–82 season Watford achieved promotion, ending the season in 2nd place, and gaining 23 wins and 11 draws in 42 games.[19]

In the First Division with Taylor as manager, Watford gained its highest-ever victory (8–0 against Sunderland)[7] as well as the "double" over Arsenal, an away win at Tottenham Hotspur, and home victories over Everton and Liverpool; this resulted in Watford finishing runners-up in the entire Football League.[20] He then took the side to the third round of the UEFA Cup, having finished second in 1982–83 (the club's first season as a top division club). Taylor also led Watford to the 1984 FA Cup final, which Watford lost to Everton 2–0.[21] In his final season, 1986–87, Watford finished ninth in the league and reached the FA Cup semi-finals, missing out on another Wembley appearance when they lost to Tottenham Hotspur, their chances hardly helped by the fact that both of their first team goalkeepers were injured.[22]

Aston Villa (1987–1990)

[edit]In May 1987, Taylor left Watford for a new challenge at Aston Villa, who had just been relegated from the First Division.[23] Second-tier football was a terrible setback for the Midlanders, who had won the European Cup just five years earlier and had been league champions six years earlier.[24]

Taylor managed to take Aston Villa back to the top flight with his first attempt, securing their top flight safety in 1988–89 with a draw on the final day of the league season.[25] During his third season at the club Villa finished runners-up in the First Division, having led the league table at several stages of the season before being overhauled in the final weeks by Liverpool.[26] Following this success, Taylor accepted an offer to take over the England national football team from Bobby Robson, who left the job after England's semi-final defeat to West Germany at the 1990 World Cup.[27]

International management: England (1990–1993)

[edit]Appointment

[edit]When Taylor was appointed, critics in the media complained that he had never won a major trophy – although he had taken teams to second place in the league twice and an FA Cup final once in 1984. It was also pointed out that Taylor had never played in "top-flight" football, let alone international level and that winning the respect of the players might be difficult. His critics also noted although he had ditched the long-ball game at Aston Villa, there were still tactical worries about his intentions, given that English clubs were looking to dispense with "route one" football in favour of a more "picturesque route to goal".[28]

1992 European Championship

[edit]Despite the unease at his appointment, England lost just once in Taylor's first 23 matches (a 1–0 defeat to Germany at Wembley Stadium in September 1991).[29] However, England struggled to qualify for Euro '92. In a group containing Turkey, Ireland, and Poland, England were held to two 1–1 draws by Ireland and managed just 1–0 wins home and away against Turkey. It was only a late goal from Gary Lineker against Poland that saw England qualify at Ireland's expense. England's qualification for the Euro 92 finals proved to be the high point of Taylor's tenure.[30]

The number of players that Taylor was using in the run up to the championship was also questioned, the press and public viewed this as evidence Taylor did not know his best team. He used 59 players in total, as he struggled to find a "new spine" after the retirement of Peter Shilton, Terry Butcher and Bryan Robson.[31] He also faced accusations he could not cope with "stars", after he dropped Paul Gascoigne for Gordon Cowans for a qualifying game against Ireland.[32] fearing he might "lose his head" in what would be a "bruising" encounter.[33] Matters were not helped by Taylor's reluctance to use creative players who were not perceived to have high work rates, such as Chris Waddle and Peter Beardsley. He also suffered several injuries, notably to Gary Stevens, Lee Dixon, John Barnes and Paul Gascoigne, leaving the squad in a makeshift position going into the finals.[34]

England were drawn to face France, Denmark and hosts Sweden in group 1. In the opening game against Denmark, England started brightly and missed several chances to take a lead. David Platt was guilty of a particularly glaring miss. Thereafter, Denmark began to dominate the match, and nearly won with minutes left as John Jensen struck a post. The game ended 0–0.[35] In the match against France, Platt nearly scored with a diving header which went inches wide of the post, and Stuart Pearce hit the bar with a free-kick. The game also ended 0–0.[36][37]

England needed to beat hosts Sweden to advance to the semi-finals. Lineker crossed for Platt to open the scoring on four minutes with a mishit volley. However, England wasted several chances to extend their lead. Platt made a pass to Tony Daley who wasted a chance to pass to Lineker in the open. England held a slender 1–0 lead at half-time.[38][39] After half-time, Sweden changed their personnel and formation, and dominated the second half, scoring twice to win 2–1 and eliminating England.[36]

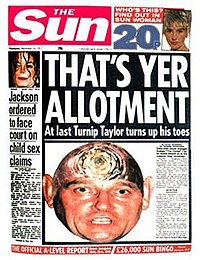

During the game, after 60 minutes and with the score at 1–1, Taylor substituted Gary Lineker in his final game for England, preventing Lineker from having the chance to equal, or possibly break, Bobby Charlton's record of 49 goals for England. Many were dismayed to see Taylor substitute England's top striker when his side needed a goal. This led to the media's vilification of Taylor, including the "turnip" campaign by The Sun, which began the morning after the game under the headline: "Swedes 2 Turnips 1". During that campaign, the newspaper's back page featured an image of Taylor's face superimposed onto a turnip.[40]

1994 World Cup Qualification

[edit]Stuttering start

[edit]

Taylor's relationship with the press was partially restored when he admitted his mistakes a few weeks after the finals.[41] However, this did not last long. England's first game after Euro 92 ended in a 1–0 defeat to Spain in a friendly, The Sun depicted Taylor as a "Spanish onion".[42]

England were drawn in Qualification Group 2 for the 1994 FIFA World Cup in the United States. The group contained Norway, the Netherlands, Poland, Turkey and San Marino. England were expected to qualify along with the Dutch.

England began with a disappointing 1–1 draw with Norway. Norway were the early pace setters, with victories over San Marino, the Netherlands and Turkey. Gascoigne returned, but the Norwegians were confident.[43] Despite dominating the game, England could muster only half-chances. Platt gave England the lead in the 55th minute after a cross from Stuart Pearce.

Norway rarely threatened, but equalised in the 77th minute, when Kjetil Rekdal scored from 20 yards. The draw flattered the Norwegians but put them clear in the group.

Three wins and a Dutch draw

[edit]The campaign seemed to get back on track with two wins against Turkey (4–0 at home and 2–0 away) and a 6–0 home victory over San Marino. During the latter game, Taylor confronted a spectator who was racially abusing Jamaica-born John Barnes, telling him "You're talking about another human being so just watch your language".[44]

In April 1993 England faced the Netherlands at Wembley Stadium. England went 2–0 up in 24 minutes through John Barnes and David Platt. However, Taylor's luck had started to take a turn for the worse, as Paul Gascoigne was injured by Jan Wouters' elbow, but Wouters was not sent off.

Dennis Bergkamp scored a goal for the Netherlands towards the end of the first half, against the run of play, but England continued to control the game, and looked to be heading for a win which would have ended Dutch hopes of qualification, following the side's defeat in Norway, and a draw at home to Poland.

But four minutes from full-time Marc Overmars outpaced Des Walker, prompting Walker to foul him inside the penalty area. The penalty was converted by Peter Van Vossen and the game ended 2–2. Suddenly England's "World Cup life" looked in danger.[42]

Draw in Poland, defeat in Norway

[edit]England's next chance of reviving their flagging fortunes came in May, requiring at least a win and draw away against Poland and Norway which were to be played just three days apart. England were poor against Poland and were largely outplayed.[45] Dariusz Adamczuk of Poland scored in the 36th minute, although the team missed several chances to extend their lead. Ian Wright salvaged a vital point through forcing an equaliser in the 85th minute, for a final score of 1–1.[45] Taylor was again vilified for his team's poor performance. England's next opponents were Norway.

The Norwegians had arrived from obscurity and had taken the group by storm; their series of early victories had left England, Poland, and the Netherlands scrapping for second place.[45] Taylor made wholesale changes of personnel and tactics, which again drew criticism, his actions considered risky in what was now a crucial game. Lee Sharpe and Lee Dixon came on as wing-backs, while Carlton Palmer and Platt occupied midfield berths. Gascoigne supported Teddy Sheringham and Les Ferdinand up-front. Des Walker, Tony Adams and Gary Pallister formed a back three.[45]

England lost 2–0, with few attempts on goal. Lars Bohinen and Øyvind Leonhardsen scored the goals in the 42nd and 47th minutes. The first was caused by a Des Walker error, while Walker was beaten for pace by a Norwegian counter-attack for Bohinen to score[46] Subsequently, Taylor said: "We made a complete mess of it. I'm here to be shot at and take the rap. I have no defence for our performance",[47] although his honesty did not spare him a roasting from the press, who were now calling for his head.[47] The press came up with headlines such as "NORSE MANURE" and "OSLO RANS".[48]

In July 1993, Peter Newman, an independent candidate in a parliamentary by-election for Christchurch, stood under the banner "Sack Graham Taylor".[49]

The US Cup

[edit]With their World Cup hopes hanging by a thread, Taylor's England were to play a four-team Tournament in the U.S (1993 U.S. Cup), which was expected to be a precursor to the following summer's tournament. Taylor stated before the game against the United States:

In football, you're only as good as your last game, and at the moment we're poor. You can always lose any game, to anyone. It's how you lose that matters. That was the thing that shocked us all in Norway. We would have been looking for a win here anyhow, but if we'd won last week, it wouldn't have been considered essential. Now it is. Whether we like it or not, people expect us to beat America, and there is definitely more intensity about this game because of our performance in the last one.[50]

For Taylor, the US Cup began with a humiliating 2–0 defeat in Boston, to the United States with Thomas Dooley and Alexi Lalas scoring goals, which was reported by The Sun as "YANKS 2 PLANKS 0!".[51][52]

Some pride was restored with a credible 1–1 draw with Brazil, and a narrow 2–1 defeat to Germany. Taylor was now living on borrowed time.[53]

Crucial match against the Netherlands

[edit]The 1993–94 season began with a much-improved performance, with a 3–0 win over Poland raising the nation's hopes going into what was now the crucial match against the Netherlands in Rotterdam.[53]

In October, England were to play the Netherlands in Rotterdam. With Norway having won the group, the encounter would effectively decide the second and last qualifier of the group. The game was played at a furious pace, with the Netherlands putting England under pressure early on. However, England hit back with a string of counterattacks, with Platt heading just wide and Tony Adams having a shot cleared off the line by Erwin Koeman, while Tony Dorigo hit a post with a deflected 35-yard free-kick after 25 minutes.[53][54]

Two minutes before half-time England were fortunate to have a Frank Rijkaard goal ruled out for offside, even though replays showed the goal was legitimate.[53] Later in the second half, with the game scoreless, David Platt was fouled by Ronald Koeman as he approached the Dutch goal. The German referee failed to apply the rule of sending him off for a professional foul. The Dutch charged down Dorigo's free kick, although they were clearly encroaching.[55] Just minutes later, Koeman took a free kick outside England's penalty area. His first shot was blocked, but it was ordered to be retaken because of encroachment.[53] Koeman scored at the second attempt.

Paul Merson hit a post with a free-kick moments later, before Dennis Bergkamp scored, despite using his arm to control the ball, for a 2–0 win.[53] In the meantime, Taylor was in an apoplectic mood on the touchline, berating the officials and referee as the significance of the result sank in.[53]

San Marino and resignation

[edit]England still had a chance to qualify, providing the Netherlands lost in Poland on the same night, with England winning by a seven-goal margin or more. As such, England were hoping they could run up a big score against part-time minnows San Marino. But after just 8.3 seconds of play David Gualtieri, a computer salesman, scored the fastest ever World Cup goal after a defensive error from Stuart Pearce. England took another twenty minutes to find an equaliser and eventually won 7–1. Even if the Netherlands had not beaten Poland, England's inferior goal difference would have still meant they had failed to qualify.[56]

Taylor resigned on 23 November 1993, six days after England's failure to qualify. He went "with great sadness", saying: "No one can gauge the depth of my personal disappointment at not qualifying for the World Cup. This is the appropriate course of action in the circumstances," he said. "If we didn't qualify, it was always my intention to offer my resignation."[57] Taylor had also agreed to be filmed during the qualifying campaign for Cutting Edge, a Channel 4 fly-on-the-wall documentary series, in which his portrayal further undermined his authority. This was during the film An Impossible Job; Taylor was heard to use foul language, and what became his personal catchphrase: "Do I not like that", uttered just before England conceded a goal to Poland.[58]

Return to club management

[edit]Wolverhampton Wanderers (1994–1995)

[edit]Sir Jack Hayward appointed Taylor as manager of Wolverhampton Wanderers in March 1994, replacing Graham Turner. Taylor had been a generally unpopular figure in English football since his unsuccessful reign as national coach, and few people seemed willing to forgive him for his first managerial failure – one that mattered most to so many people up and down the country. But the following season Taylor took the Midlands club to fourth in Division One to qualify for the playoffs – their highest league finish since their last top division season eleven years earlier – where they lost out to Bolton Wanderers. They also reached the quarter-finals of the FA Cup after a memorable replay penalty shootout victory over Sheffield Wednesday, in which they were 3–0 down on penalties, only to win the shootout 4–3, in which Chris Bart-Williams had two penalties saved over the two matches.

Taylor spent heavily on players while at Wolves, paying large sums for the likes of Steve Froggatt, Tony Daley, Mark Atkins, John de Wolf, Dean Richards and Don Goodman.[59]

However, the 1994–95 season proved to be his only full season at Molineux, as, after a poor start to the following campaign, winning just four of the first sixteen league games, he resigned on 13 November 1995 due to overwhelming supporter pressure. During his tenure, he attempted to perform a citizen's arrest on a fan who had spat at him, prompting calls for closer crowd controls in the English game.[60]

Taylor called his Wolves' departure his "lowest ebb" in football - greater than even his Lancaster Gate exit - because he felt he had "lost his standing" in the game of football.[61]

Return to Watford (1996–2001)

[edit]In February 1996 Elton John, who had recently bought Watford for a second time, appointed Taylor as General Manager at Vicarage Road. Just over a year later Taylor had appointed himself as the club's manager succeeding Kenny Jackett, who was relegated to a coaching capacity at the club. Taylor later stated that the role of General Manager had "bored me stiff".[62] He won the Division Two championship at his first attempt in 1998.[63]

The following season Watford won the Division One Play-off Final, beating Bolton Wanderers 2–0 at Wembley, and with it promotion to the Premier League. Taylor missed two months of the season as in November 1998 he was taken to hospital with a life-threatening abscess that blocked his windpipe and almost killed him.[64]

Watford were relegated from the Premiership after one season.[65] Despite starting the following season well – unbeaten through the first fifteen league games and heading the table – Watford slumped to finish 9th in Division One.[66] At this point he decided to retire.[67] During this final season Taylor had become only the third manager to manage 1,000 league games in England, after Brian Clough and Jim Smith.[68]

Return to Aston Villa (2002–2003)

[edit]Taylor came out of retirement in February 2002 to return to his old job at Aston Villa, but retired for a second time after Villa finished the 2002–03 season in 16th place in the Premiership.[69] He subsequently cited tensions in his relationship with the club's chairman Doug Ellis and argued for an overhaul of the club's upper management to allow the club to be more competitive.[70]

Later life

[edit]

In 2003, Taylor became vice-president at Division Three club Scunthorpe United, his hometown club.[71] From 2004, he worked as a pundit on BBC Radio Five Live,[21] and managed a team of celebrities for Sky One's annual series, The Match.

His time at Scunthorpe saw a turnaround in the club's fortunes. In his first season on the board, they narrowly avoided relegation to the Conference. The following season, they were promoted to League One. Two years after that, they were promoted to the Championship as League One champions.[72]

Taylor returned to Watford on 23 January 2009, being appointed to the new board as a non-executive director and was appointed interim chairman on 16 December 2009.[73] Taylor announced his resignation from his position as chairman on 30 May 2012. He retained the position of honorary life president of the club until his death in 2017.[74]

In 2014, Watford renamed the Rous Stand the Graham Taylor Stand to honour his achievements in two spells at the club.[21]

Other work

[edit]Taylor was a supporter of Sense-National Deafblind and Rubella Association and a Patron of DebRa. He was a Celebrity Ambassador for the Sense Enterprise Board in Birmingham, and worked to raise both funds and awareness, including running the London Marathon in 2004.[75] He regularly hosted moderated "online coaching seminars" on the DALnet channel. He also supported the Royal British Legion and cycled from London to Paris in 2010 to raise funds for the RBL's Poppy appeal.[76]

Personal life and death

[edit]Taylor married Rita Cowling at Scunthorpe Congregationalist Church on 22 March 1965.[77] They had two daughters.[78]

Taylor died suddenly and unexpectedly of a "suspected heart attack"[79] at his home in Kings Langley early on the morning of 12 January 2017. He was 72.[80][81][82] His funeral was held nearby, on 1 February at St Mary's Church, Watford, with many football figures in attendance.[83]

Honours

[edit]As a manager

[edit]- Lincoln City

- Football League Fourth Division Champions: 1975–76

- Watford

- Football League Fourth Division Champions: 1977–78

- Football League Third Division Runners-up: 1978–79

- Football League Second Division Runners-up: 1981–82

- Football League First Division Runners-up: 1982–83

- FA Cup Runners-up: 1984

- Football League Division Two Champions: 1997–98

- Football League Division One Play-off winner: 1998–99

- Aston Villa

- Football League Second Division Runners-up: 1987–88

- Football League First Division Runners-up: 1989–90

Managerial statistics

[edit]| Team | From | To | Record | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G | W | D | L | Win % | |||

| Lincoln City | Dec 1972 | Jun 1977 | 236 | 104 | 69 | 63 | 44.07 |

| Watford | Jun 1977 | May 1987 | 527 | 244 | 124 | 159 | 46.30 |

| Aston Villa | May 1987 | Jul 1990 | 142 | 65 | 35 | 42 | 45.77 |

| England | Jul 1990 | Nov 1993 | 38 | 18 | 13 | 7 | 47.37 |

| Wolverhampton Wanderers | Mar 1994 | Nov 1995 | 88 | 37 | 27 | 24 | 42.05 |

| Watford | Feb 1996 | Jun 1996 | 18 | 5 | 8 | 5 | 27.78 |

| Watford | Jun 1997 | May 2001 | 202 | 79 | 52 | 71 | 39.11 |

| Aston Villa | Feb 2002 | May 2003 | 60 | 19 | 14 | 27 | 31.67 |

| Total | 1,311 | 571 | 342 | 398 | 43.55 | ||

Further reading

[edit]- Birnie, Lionel (2010). Enjoy the Game – Watford FC, The Story of the Eighties. Peloton Publishing. ISBN 978-0-9567814-0-6.

- Phillips, Oliver (2001). The Golden Boys: A Study of Watford's Cult Heroes. Alpine Press Ltd. ISBN 0-9528631-6-2.

- Phillips, Oliver (1991). The Official Centenary History of Watford FC 1881–1991. Watford Football Club. ISBN 0-9509601-6-0.

- England: The Official F.A History, Niall Edworthy, Virgin Publishers, 1997, ISBN 1-85227-699-1.

- Gary Lineker: Strikingly Different, Colin Malam, Stanley Paul Publications, London, 1993 ISBN 0-09-175424-0

- Do I not Like That – The Final Chapter, Chrysalis Sport, Distributed by Polygram Record Operations, 1994.

References

[edit]- ^ Tongue, Steve (12 January 2017). "Graham Taylor flourished at Watford and Aston Villa – his legacy will live long at these two clubs". The Independent. Archived from the original on 14 January 2017. Retrieved 13 January 2017.

- ^ a b McNulty, Phil (12 January 2017). "Graham Taylor obituary: Ex-England boss a fount of knowledge and a true gentleman". BBC. Archived from the original on 12 January 2017. Retrieved 12 January 2017.

- ^ Taylor, Graham (19 February 2005). "Taylor on Saturday". Daily Telegraph. London. Retrieved 16 March 2008.[dead link]

- ^ Edworthy, p. 156

- ^ "Ex-England football manager Graham Taylor on his best teacher: Mr Warburton". TES. 11 June 2016. Archived from the original on 13 January 2017. Retrieved 12 January 2017.

- ^ "Profile: Graham Taylor – The turnip strikes back". The Independent. Archived from the original on 17 November 2015. Retrieved 2 December 2015.

- ^ a b "Graham Taylor OBE: 1944–2017". EFL. 12 January 2017. Archived from the original on 13 January 2017. Retrieved 12 January 2017.

- ^ a b "Graham Taylor: Former England manager dies at the age of 72". BBC Sport. 12 January 2017. Archived from the original on 12 January 2017. Retrieved 12 January 2017.

- ^ The Guardian - 8 December 1972

- ^ a b Graham Taylor - in his own words (2017).

- ^ "On this day in history ~ Division Four, 1976". When Saturday Comes. 10 January 2015. Archived from the original on 13 January 2017. Retrieved 12 January 2017.

- ^ "Former Lincoln City and England boss Graham Taylor to have Watford stand named after him". Lincolnshire Live. 1 May 2014. Retrieved 12 January 2017.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "First & last: Graham Taylor". The Guardian. 1 July 2006. Archived from the original on 27 September 2016. Retrieved 21 September 2016.

- ^ "Former England manager Graham Taylor mourned". UEFA.com. 12 January 2017. Archived from the original on 13 January 2017. Retrieved 14 January 2017.

- ^ "English Division Four (old) 1977–1978". Statto.com. Archived from the original on 28 July 2016. Retrieved 12 January 2017.

- ^ "English Division Three (old) 1978–1979". Statto.com. Archived from the original on 13 January 2017. Retrieved 12 January 2017.

- ^ "English Division Two (old) 1979–1980". Statto.com. Archived from the original on 13 January 2017. Retrieved 12 January 2017.

- ^ "English Division Two (old) 1980–1981". Statto.com. Archived from the original on 13 January 2017. Retrieved 12 January 2017.

- ^ "English Division Two (old) 1981–1982". Statto.com. Archived from the original on 9 April 2017. Retrieved 12 January 2017.

- ^ "Watford 1982–1983". Statto.com. Archived from the original on 13 January 2017. Retrieved 12 January 2017.

- ^ a b c "Graham Taylor: England manager who worked Watford miracle". Sky Sports. 12 January 2017. Archived from the original on 13 January 2017. Retrieved 12 January 2017.

- ^ White, Jim (26 January 2012). "Jim White: Watford comeback king Gary Plumley recalls FA Cup heroics against Spurs". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 13 January 2017. Retrieved 12 January 2017.

- ^ Lovett, Samuel (12 January 2017). "Graham Taylor dead: Former England and Aston Villa manager dies at 72". The Independent. Archived from the original on 14 January 2017. Retrieved 12 January 2017.

- ^ Pye, Steven (26 May 2016). "How Aston Villa won the European Cup (and were then relegated five years later)". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 22 June 2017. Retrieved 12 January 2017.

- ^ "Aston Villa 1988–1989". Statto.com. Archived from the original on 13 January 2017. Retrieved 12 January 2017.

- ^ "Aston Villa 1989–1990". Statto.com. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 12 January 2017.

- ^ "Graham Taylor, former England manager, dies at the age of 72". The Guardian. 12 January 2017. Archived from the original on 12 January 2017. Retrieved 12 January 2017.

- ^ Edworthy, pp. 14–147

- ^ Edworthy, p. 148

- ^ Edworthy 1997, p. 148.

- ^ Edworthy 1997, p. 156.

- ^ Edworthy 1997, p. 149.

- ^ Edworthy 1997, p. 1150.

- ^ Kelly, Ciaran (6 March 2012). "Graham Taylor and the impossible job". BackPageFootball. Archived from the original on 13 January 2017. Retrieved 12 January 2017.

- ^ Granville, Brian England's Managers: The Toughest Job in Football 2007, ISBN 978-0-7553-1651-9 p. 176.

- ^ a b "Norman Giller's England Lineups and Match Highlights 1990-91 to 1995-96". Archived from the original on 2 October 2012. Retrieved 24 February 2012.

- ^ "World Cup failure still haunts Taylor". New Sabah Times. 9 October 2013. Archived from the original on 9 October 2013. Retrieved 9 October 2013.

- ^ "England Match No. 688 - Sweden - 17 June 1992 - Match Summary and Report". Englandfootballonline.com. Archived from the original on 4 January 2010. Retrieved 14 January 2017.

- ^ Granville, Brian England's Managers: The Toughest Job in Football 2007, ISBN 978-0-7553-1651-9 p. 177.

- ^ Edworthy, p. 149

- ^ Malam, pp. 120–121

- ^ a b Edworthy, p. 151

- ^ Joe Lovejoy. "Football: England turn to Gascoigne for dream start". The Independent. Archived from the original on 25 June 2017. Retrieved 14 January 2017.

- ^ "Football mourns Graham Taylor: Farewell to a gentleman". Telegraph. 12 January 2017. Archived from the original on 12 January 2017. Retrieved 13 January 2017.

- ^ a b c d Edworthy, p. 152

- ^ Lovejoy, Joe (3 June 1993). "Norway destroy Taylor's England: Calamity in Oslo as a revamped team collapses in the face of Scandinavian skill". The Independent. London. Archived from the original on 25 September 2015. Retrieved 29 August 2017.

- ^ a b Edworthy, p. 153

- ^ Do I Not Like That -The Final Chapter

- ^ "Profile: Graham Taylor – The turnip strikes back". The Independent. 7 August 1999. Archived from the original on 25 September 2015. Retrieved 29 August 2017.

- ^ Lovejoy, Joe (9 June 1993). "Football: Batty given the safety-pin role for belt-and-braces England: Walker and Sheringham dropped in wake of Norway humiliation as US Cup opener against United States becomes of vital importance to Taylor's tenure". The Independent. London. Archived from the original on 5 November 2012. Retrieved 4 May 2010.

- ^ Trevor Haylett (24 November 1993). "Football: The painful failure of a proud man: Trevor Haylett on the highs and lows in Graham Taylor's career". The Independent. Archived from the original on 12 November 2012. Retrieved 14 January 2017.

- ^ Joe Lovejoy (10 June 1993). "England's new low as US pile on the misery". The Independent. Archived from the original on 6 June 2010. Retrieved 23 June 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f g Edworthy, p. 154

- ^ "Football: News, opinion, previews, results & live scores – Mirror Online". Mirrorfootball.co.uk. Archived from the original on 13 December 2021. Retrieved 14 January 2017.

- ^ Glanville, Brian. England Managers: The Toughest Job in Football, p. 185.

- ^ Bevan, Chris (11 October 2012). "Davide Gualtieri: The man from San Marino who shocked England". BBC Sport. Archived from the original on 20 November 2015. Retrieved 13 January 2017.

- ^ Joe Lovejoy. "Football: Howe set to become England caretaker: Taylor accepts the inevitable and tenders resignation as FA considers its options with chief executive favouring two-tier administration". The Independent. Archived from the original on 5 July 2017. Retrieved 14 January 2017.

- ^ "Do I not like that? The documentary that charted Graham Taylor's England career". Eurosport. 13 January 2017. Archived from the original on 13 December 2021. Retrieved 13 December 2021.

- ^ "Wolves Managers from 1885 to Today". Archived from the original on 2 October 2011. Retrieved 1 September 2011.

- ^ Duxbury, Nick (25 April 1995). "Tait's 'prank' finishes with an FA charge". The Independent. London. Archived from the original on 22 January 2010. Retrieved 4 May 2010.

- ^ "Wolves ghost eludes Taylor". The Guardian. 30 October 2000. Archived from the original on 1 August 2020. Retrieved 8 September 2019.

- ^ Phillips, Oliver (4 January 2017). "Further reflections on Watford's 2002/03 campaign focus on the role of Terry Byrne". Watford Observer. Newsquest. Archived from the original on 7 January 2017. Retrieved 12 January 2017.

- ^ "Watford 1997–1998". Statto.com. Archived from the original on 13 May 2017. Retrieved 12 January 2017.

- ^ "Taylor's brush with death". The Independent. 23 December 1998. Archived from the original on 13 December 2021. Retrieved 29 August 2017.

- ^ "Watford 1999–2000". Statto.com. Archived from the original on 13 January 2017. Retrieved 12 January 2017.

- ^ "Watford 2000–2001". Statto.com. Archived from the original on 13 January 2017. Retrieved 12 January 2017.

- ^ a b "Graham Taylor OBE". League Manager's Association. Archived from the original on 22 March 2017. Retrieved 12 January 2017.

- ^ "Tony Pulis joining a select club – managers who have reached 1,000 games milestone in English football". The Daily Telegraph. 23 September 2016. Archived from the original on 13 January 2017. Retrieved 12 January 2017.

- ^ "Taylor quits Villa". BBC Sport. 14 May 2003. Archived from the original on 4 September 2020. Retrieved 8 December 2007.

- ^ "People think they know me, but they don't' – Graham Taylor interview". The Guardian. 22 September 2002. Archived from the original on 13 January 2017. Retrieved 13 January 2017.

- ^ "Graham Taylor dies aged 72: Scunthorpe tributes paid to former England manager". Scunthorpe Telegraph. 12 January 2017. Archived from the original on 13 January 2017. Retrieved 12 January 2017.

- ^ "Scunthorpe United history". Statto.com. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 12 January 2017.

- ^ [1] Archived 25 January 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Watford Football Club". Watfordfc.com. Archived from the original on 26 November 2015. Retrieved 14 January 2017.

- ^ Harper, Nick (23 January 2004). "Graham Taylor". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 18 January 2017. Retrieved 12 January 2017.

- ^ Macaskill, Sandy (2 September 2010). "Kevin MacDonald backed for Aston Villa hotseat by Graham Taylor". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022. Retrieved 12 January 2017.

- ^ Grimsby Evening Telegraph Tue, 23 Mar 1965 ·Page 6

- ^ Cornwell, Rupert (6 August 1999). "Profile: Graham Taylor – The turnip strikes back". The Independent. Archived from the original on 14 September 2017. Retrieved 13 September 2017.

- ^ "Former England manager Graham Taylor dies of suspected heart attack". Sky News. Retrieved 12 November 2023.

- ^ "Graham Taylor: Former England manager dies at 72". BBC Sport. 12 January 2017. Archived from the original on 27 March 2018. Retrieved 13 February 2018.

- ^ "Graham Taylor obituary". The Guardian. 12 January 2017. Archived from the original on 12 January 2017. Retrieved 13 January 2017.

- ^ "Graham Taylor: Sir Elton John says former England boss was 'like a brother to me'". BBC Sport. 12 January 2017. Archived from the original on 12 January 2017. Retrieved 12 January 2017.

- ^ "Graham Taylor funeral: Crowds gather for England boss". BBC Sport. 1 February 2017. Archived from the original on 14 September 2017. Retrieved 13 September 2017.

- ^ "Graham Taylor". Managers. Socceerbase. Archived from the original on 16 January 2017. Retrieved 14 January 2017.

External links

[edit]- Graham Taylor at Soccerbase

- Graham Taylor management career statistics at Soccerbase

Lua error in Module:Navbox at line 192: attempt to concatenate field 'argHash' (a nil value).

Lua error in Module:Navbox at line 192: attempt to concatenate field 'argHash' (a nil value). Error: Module:Navbox:192: attempt to concatenate field 'argHash' (a nil value) at Template:Lincoln City F.C. managers

Error: Module:Navbox:192: attempt to concatenate field 'argHash' (a nil value) at Template:Watford F.C. managers

Error: Module:Navbox:192: attempt to concatenate field 'argHash' (a nil value) at Template:Aston Villa F.C. managers

Error: Module:Navbox:192: attempt to concatenate field 'argHash' (a nil value) at Template:England national football team managers

Error: Module:Navbox:192: attempt to concatenate field 'argHash' (a nil value) at Template:Wolverhampton Wanderers F.C. managersLua error in Module:Navbox at line 192: attempt to concatenate field 'argHash' (a nil value). Lua error in Module:Navbox at line 192: attempt to concatenate field 'argHash' (a nil value).

- 1944 births

- 2017 deaths

- UEFA Euro 1992 managers

- England national football team managers

- English football managers

- English Football League managers

- Premier League managers

- Aston Villa F.C. managers

- Lincoln City F.C. managers

- Watford F.C. managers

- Watford F.C. directors

- English men's footballers

- Grimsby Town F.C. players

- Wolverhampton Wanderers F.C. managers

- Lincoln City F.C. players

- Footballers from Worksop

- Officers of the Order of the British Empire

- Footballers from Scunthorpe

- English Football League players

- English Football Hall of Fame inductees

- English association football commentators

- Men's association football fullbacks

- Aston Villa F.C. directors and chairmen

- 20th-century English sportsmen